I asked Vani how she felt about the caged humans.

“It’s painful. It’s an emotional abortion. It’s disgusting.”

If that’s your answer then, “still you want to visit? “

“Yeah,” she said. “I could use some disgusting.”

Dad gave his me the car when I told him I was taking Vani. He put the keys in my palm. He put a handful of change in my other hand.

“To feed the animals,” he said.

Vani smoked cigarettes all the way to the caged domain. She cracked the window barely and flicked ash into the wind. She burned the roof of my alto in at least four different places. “Sorry,” she said each time, but she didn’t use any more precaution than she had before.

It was rainy and the visible parts of Indian Ocean were flooded almost fifteen feet onto the shore. Plantation rose from the water like they were meant for life in the swamp. The waste that flowed through the ocean was creeping up toward the highway and the smell mixed with the cigarette smoke. I breathed in deep to get a trace of Vani. The stink never stuck to her. She didn’t even smell of grease though she worked just much time as me in the kitchen as I did. I was now a reeking mess of lard fumes and cigarette smoke and ocean stench. Vani flicked a butt out the window. Of course it hit the door frame before exiting, raining a shower of tiny red cherry specks and leaving dark pinhole spots on the seat. I watched in the rear view for a methane explosion. Something violent that would ignite the whole ocean, adding the smell of burning rubber as the old fishermen in their waders burned away to nothing. It didn’t happen and I looked over at her. She felt my eyes and met them.

“What?”

“Nothing.” And I wondered how she pulled thoughts out of me by the handful and pushed them against some giant light canvas, exposing the ridiculous in me in vivid detail.

“Want one?” she said holding out the pack, showing me the cancer ridden pancreas on the front.

“Sure.” Maybe I’d have better luck setting the fire.

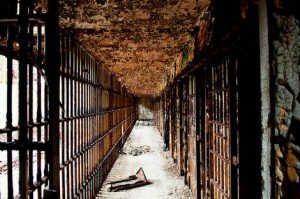

We entered the domain of countless cages. The place was gray and dead. The cold wind met us head on through every twist and turn of the concrete path. Family units found us with their gaze, a polite smile creeping up on defeated lips.

At the fowl pond the convicts sat in the cooling water naked, their necks collared in leather and chained to the rock façade behind them. They were mostly fishermen, not the hostiles, but those who had tried to stay after the big border wall closed for good. They’d been warned. It was almost ten years now, but the ads had been everywhere: The Man himself on the tube, telling them, “Go home. We don’t want you here anymore. Go back to where you came from.” I guessed the fowl pond was full of these hangers on because they just wouldn’t leave, and now they were chained up in the water and their fingers were cut off, a symbolic wind clipping that prevented them from leaving if they wanted to. Vani and I watched them. They looked pathetic sitting in their own filth, waiting to catch some water-borne illness and die, flat fingerless hands stroking the water for comfort.

I used the change Dad had given me and I bought a rupees worth of feed from the coin-op machine, twisting the handle and getting a handful for fifty paise. I gave some to Vani and we tossed it into the dirty water, watched the captives climb all over each other for the scraps of waterlogged bran or whatever meal it was. They tried to gouge out each other’s eyes with phantom fingers. They cried out in squawks as we walked away. Even with tongues cut out and vocal cords scraped raw and scarred, they still tried to speak.

It was the same type of scene throughout. On Nicobar island the naked residents shivered, their hands cut off and sewn on their ankles. The reptile house with snake people stripped of their limbs. All the habitats that once housed a big cat or wolf or wolverine were filled with chained people who were hostile in some way or another. The aquarium was packed full of men and women and kids, underwater, just enough air above the surface to poke up a nostril or lips and take a breath before being yanked down by the next beast struggling for breath and trying to keep the dead at bay lest they float up and squat below the most valuable real estate.

Vani and I rested on a glossy, plastic bench fashioned to look like a log. Across from us was the Dolphin habitat. The man inside paced behind the glass, back and forth, licking his chops, growling. The info plaque stated he was a rebel, a dissident responsible for the deaths of over fifty wall builders. His fate was the smashing of his pelvis and femurs, never puzzled back together, giving him no choice but to move like the stalking big cat he’d resembled in life. Two young zookeepers walked by on patrol, hands on their assault rifles. They paid us little mind. Vani watched them walk by.

“I wanted to get assigned here,” she said.

“I thought you said it was ‘disgusting’.”

“I know. Maybe that’s why. Because they wouldn’t have me. I came here a lot when I was a kid. Lots of people on our side of the glass. Now this. It doesn’t feel right, does it?”

“I wouldn’t want to be here,” I said. “But, they have to go somewhere. We let them walk the street and it’s chaos.”

She laughed.

“You know what I mean.” I said. “More chaos. These people did something to get here.”

“Maybe. But what if they had succeeded? It might be us. They’re victims of their politics.”

“We all are I think.”

She thought about that. “Maybe. But to live this life? What warrants that?”

I read the large plaque hung above. “Treason. Murder.” I pointed to the pacing animal. “In his case.”

Vani nodded. She stood and moved to the enclosure, climbed over the metal rail and put her cheek to the glass. The man stopped pacing, rested in front of her. Vani stroked the length of his body, again and again, hand squeaking on the glass. And I envied the tiger man. If given the order I’d break him all over again.

“Let’s go,” I said. Something in my tone pulled her away, anger that maybe she mistook for confidence, safe and separate from my rival by four inches of reinforced glass. Vani smiled, still stroking the broken cat, that man, but looking at me. I again wondered how she had the ability to expose me to myself. I didn’t know what she wanted from me: a companion, a partner in commiseration, honesty with someone other than the mirror. How could I have known anything else? She was Vani and she was beautiful and she moved me in a way that made me think the end of the world was my idea. That’s a gift. To let a man think his destruction is his own doing. But that was her gift. She was my very own Vani. No, just Vani.